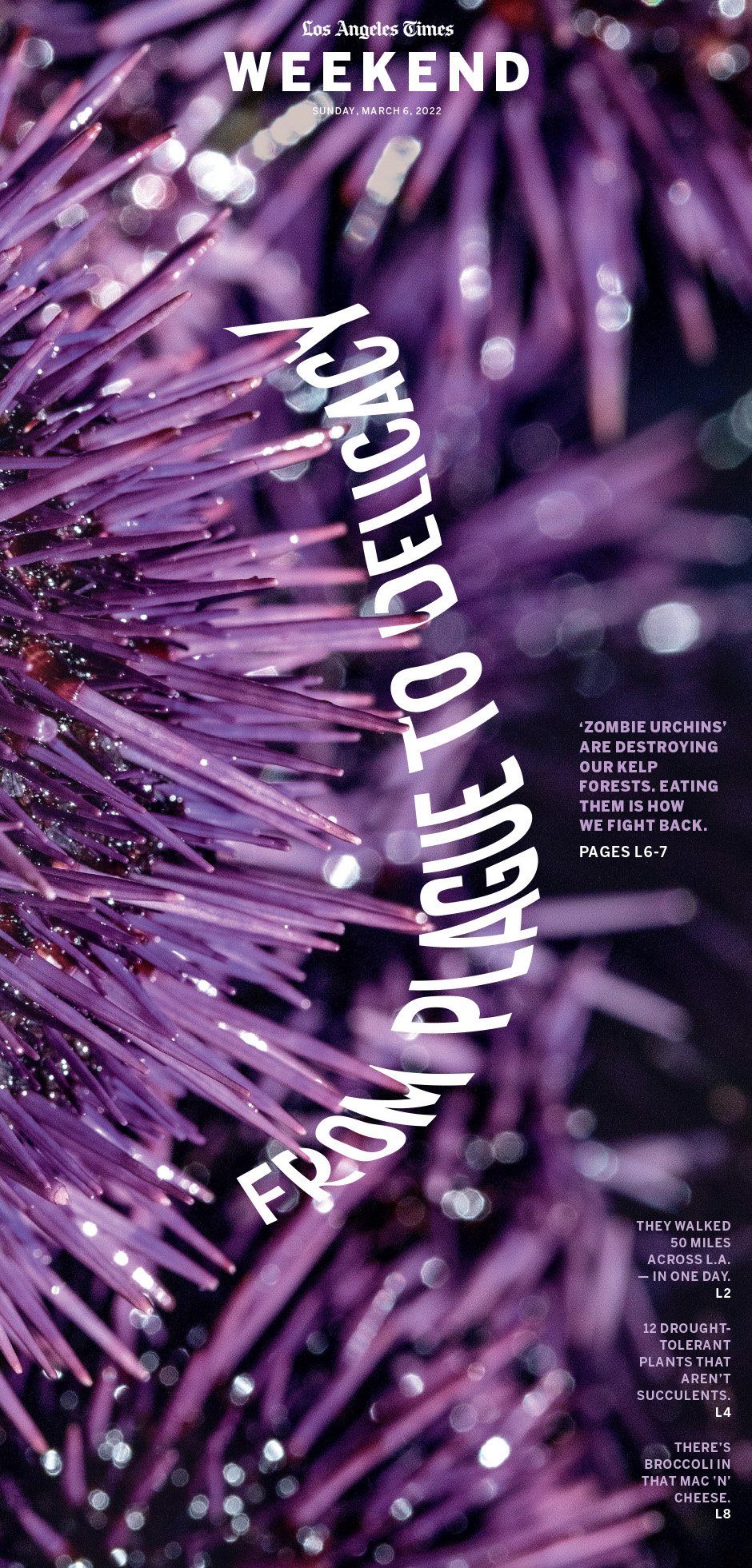

Photo by Ricardo DeAratanha of the Los Angeles Times

By Aliza Abarbanel

GOLETA, Calif. — Draped atop pillows of sushi rice or displayed in its forebodingly spiny seven-inch shell, the ubiquity of red sea urchin at high-end sushi restaurants and raw bars is a symbol of California’s coastal bounty.

But while seafood lovers might debate the merits of Kumamoto and Kusshi oysters over happy hour, considerably less attention is paid to uni varieties — unless you make a living from the ocean. Anyone who falls into that category likely knows the purple urchin too: as a ravenous source of dramatic kelp-forest devastation.

Kelp forests collect in dense patches on rocky reefs that resemble towering underwater sequoias. They can stretch for miles, providing essential food and shelter for marine life around the world. But only 5% of Northern California’s kelp forests remain today, replaced by vast “urchin barrens” where spiny purple urchins alone cover the sea floor off the coast of places like Mendocino and Sonoma counties.

“In a healthy ecosystem, the threshold for purple urchins is two per square meter,” says Norah Eddy, associate director of the Nature Conservancy’s California Oceans Program, which works with scientists and conservationists to improve fisheries and ocean health. “What we are seeing in practice on the North Coast is 60 to 100 times that.”

Marine biologists attribute this grim phenomenon to a “perfect storm” of events.

In 2014, a warm water event called “the Blob” descended over the Pacific Ocean, from Mexico to Alaska, creating high temperatures that restricted the growth of kelp. Then came the breakout of sea star wasting disease, which devastated the sunflower sea star, a primary predator of purple urchins. Left unchecked, the purple urchins devoured kelp forests in Northern California, and have begun moving southward toward the Channel Islands and Los Angeles.

The biological and financial effects on marine ecosystems have been devastating; in 2019, California closed its red abalone fishery, which was estimated to contribute $44 million to the coastal economy each year.

Nicknamed “zombie urchins” for their ability to live dormant for years without food, these purple urchins contain very little roe — which is eaten as uni — and are thought to be commercially and culinarily worthless. Desperate to keep their population in check, some conservationists have resorted to hiring divers to smash purple urchins with hammers.

But there’s another solution: Eat them.

While aquaculture and capture fisheries (a.k.a. wild fishers) are often thought of as opposing forces by consumers and the media, both entities are necessary to transform zombie urchins into buttery uni. In Goleta, the Cultured Abalone Farm partners with local divers Stephanie Mutz and Harry Liquornik to pluck nutrient-starved purple urchins from the barrens.

Biologist Doug Bush, a partner-owner in the farm, grows an array of umami-rich seaweeds to fatten the urchins up in a process called “ranching.” After 10 weeks, the zombie urchins are transformed into delicately sweet uni and delivered to restaurants like the Michelin-starred kaiseki restaurant n/naka and Malibu’s Broad Street Oyster Co.

“What we’re trying to do is acknowledge that purple urchins are an underutilized or underappreciated member of the California marine community,” Bush says. “Their roe is spectacularly good and flavorful.”

Bush first had a short stint ranching purple urchin in 2008 for the academic embryology research market, shipping small quantities to MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and Brown University. It wasn’t worth the effort. Then the marine community began raising the urchin barren alarm.

“We thought, ‘What if we brought in urchins from the barrens where there’s nothing in them and just fed them to fill them up like little cream puffs of briny deliciousness?’” says Bush. “Our work farming abalone and seaweed taught us which flavors come from eating different seaweed, so we’re able to create not just urchins that are full of roe but urchins that are full of really delicious roe.”

It all starts at sunrise. Mutz and Liquornik head out to the Channel Islands to dive for red urchin, spiny lobster and the other seafood they provide to top restaurants across the state before heading to urchin barrens spotted on previous trips. Hooked up to a hookah air compressor that delivers air through a long hose, they plunge down 30 or 40 feet to pluck the purple urchin with gloved hands.

Mutz and Liquornik bring Bush batches of 200 to 1,000 purple urchins at a time from the barrens; they’re fed in tanks that pipe in seawater from 40 feet offshore.

While wild urchin of all colors are something of a gamble — those thick spiny shells could be overflowing with buttery roe or they could be close to empty, and even judging by weight is difficult — feeding urchin from the barrens is close to a sure bet. The first lines of roe development appear in two weeks, which turn into five plump tongue-like “lobes” after 10 to 12 weeks.

Urchin ranching allows for greater control over flavor too. As with grass-fed beef or acorn-fed Iberico ham, uni’s flavor stems from its diet.

Omnivorous urchins feast on everything from seaweed to plankton in the wild, so starting with empty urchins plucked straight from the barrens provides a clean slate of flavor.

Bush grows two types of seaweed to feed his crop an all-you-can-eat buffet: dulse and ogo, two umami-rich species of red seaweed often used for furikake and poke. He supplements that with brown Macrocystis (the giant kelp often seen washed up on the beach), sustainably harvested from kelp beds. The resulting roe is a vibrant reddish orange and uncommonly sweet.

Today, Mutz offers both kinds of urchins to chefs and her pop-up market customers, branded in partnership with Bush as Purple Hotchi after hotchi-witchi, the Roma word for hedgehog. Bold home cooks can purchase live urchins through the Cultured Abalone’s website. When bad weather keeps Mutz and Liquornik on land and unable to dive for red urchin, like over New Year’s, the ranched Purple Hotchis are unaffected.

“That pleases a lot of restaurants because they don’t have to take urchin off the menu,” Mutz says. “It gives us this great opportunity to educate the public on this other species using chefs, which we’ve done since day one.”

Many restaurants prefer to work with packaged uni, which is processed at coastal facilities and arrives in a neat tray. Live urchin has a fresher, more vibrant flavor but requires delicate handling.

First, there’s the matter of breaking into that spiny shell and scooping out the lobes intact. These must be rinsed, but urchins have no osmotic control to restrict water from entering cell membranes, so even a few splashes of tap water will blow apart the delicate uni into wispy confetti. Instead, chefs use a saltwater solution — 32 grams of salt per liter — that mimics the salinity of the ocean.

Mutz says that most chefs still prefer the red urchin, which is the largest species of urchin in the world and has a higher individual yield.

“It’s taken us a long time to get chefs to even consider using urchin out of the shell instead of processed urchin from a tray,” Mutz says. “Now there’s a little adjustment with the purple urchin, and restaurants are just trying to keep open in general.”

Christopher Tompkins has been using the Cultured Abalone’s purple urchin since Broad Street Oyster Co.’s early pop-up days five years ago. “I find the purple urchin to be very sweet and plump, and while the reds can be hit or miss, their consistency is on point urchin after urchin,” Tompkins says. “They come in a smaller package so we like to use them as an add-on.”

He offers uni as a topping to imbue buttery lobster rolls or rich uni pasta with an extra hit of briny richness. It also often appears on Broad Street Oyster Co.’s statuesque seafood tower.

At n/naka in Los Angeles, urchin is sometimes draped atop raw oysters on the half shell, or steamed as a mushimono with sweet horsehair crab and starchy toro.

“We used purple urchin a lot in our takeout days because we wanted a specific size uni for the box. Now we prefer the bigger red ones because we process our urchin by hand, but anytime Stephanie is unable to get a red urchin, I’m happy to take the purple ones,” says chef Niki Nakayama of n/naka.

“The sweetness, texture and even sizing is all delicious. Especially when you find a really great one, there’s nothing like it,” Nakayama says.

The Cultured Abalone isn’t the only aquaculture farm getting into urchin ranching. Urchinomics, a company founded by Brian Tsuyoshi Takeda with a global approach, currently operates two commercial urchin ranching sites in Japan. A pilot-scale ranch is underway near Port Hueneme in partnership with the Bay Foundation, and additional trials are ongoing in Norway, Australia and Mexico, targeting barrens caused by overfishing predatory species and climate change.

There’s some good news: Bull kelp grows incredibly fast. The annual seaweed grows from a spore into maturity in just a year, sometimes 10 inches in a day. We can’t eat our way to a revitalized kelp forest alone, but as the appetite for uni grows in Los Angeles and worldwide, stepping in on behalf of the sunflower sea star to allow kelp the opportunity to grow can make eating urchin even more tempting.

“Conducting marine restoration is incredibly logistically challenging, and therefore it’s incredibly expensive,” says Eddy, of the Nature Conservancy. “These market-based solutions to reducing the purple urchin population can reduce the cost of restoration and make it more feasible to actually conduct restoration at the scale we need to see it occur.”

Last year, the Nature Conservancy performed an analysis that found that urchin ranching has the potential to offset the cost of removal by 30% if conducted at scale.

Eddy’s team is now partnering with California Sea Grant and Bush to explore ways to replicate this urchin ranching model across the state. They hope to target specific areas that have a high likelihood of seeing kelp recover if urchins are removed and kelp spores are released, starting off the north coast that stretches from San Francisco Bay to the Oregon border.

“A purple urchin that is landed, fed and sold in a restaurant creates economic benefit for everyone involved in that chain and displaces the need for seafood resources to be imported into California,” says Bush. “It’s a cherry on top that it is also a delicacy of the highest order.”